|

I still meet designers pretending they don’t need technical packages. I say pretending because they know they should have a tech pack but they either don’t have time to create a tech pack or don’t know where to start. I hear statements like; “I’m working with a local factory, they said they don’t need one”. “I don’t know how and no one has asked for one”. So, what is a tech pack and why do you need one? The tech pack is a written document that contains information about an apparel style. You will also here it called a specification or spec, Some people refer to the spec as only the finished garment measurements. There are usually a few key elements to a full technical package:

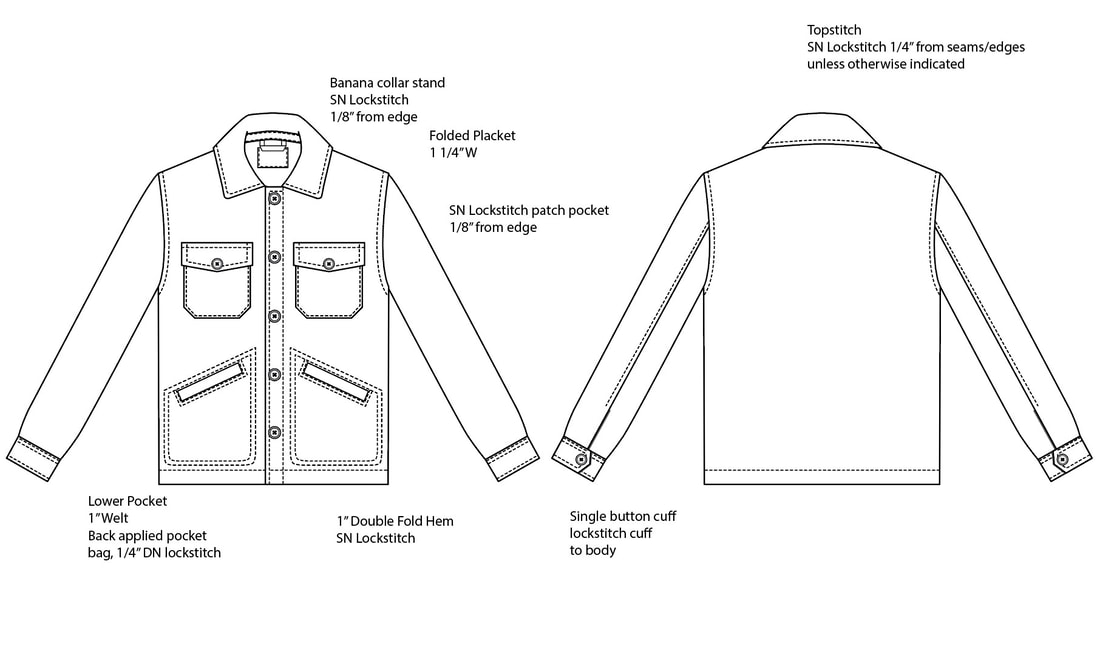

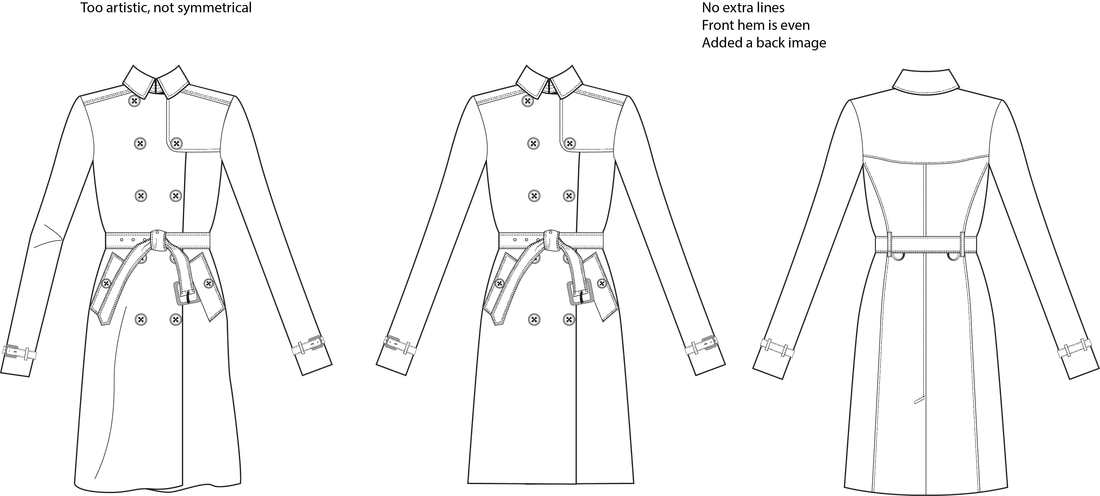

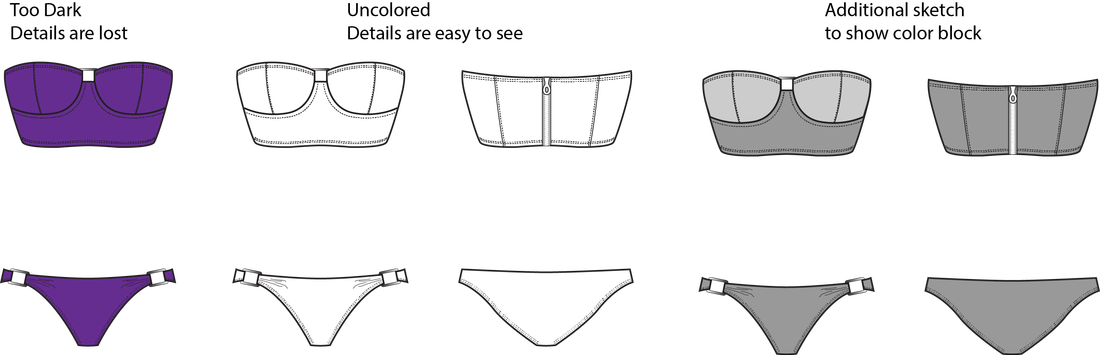

Illustrations The minimum of illustrations is the front and back of the garment. The sketches should include all construction elements, such as topstitching. The sketches should be black and white so all the details can be clearly seen and interpreted. If you want to include colored images, those should be on an additional page. Other images you might include:

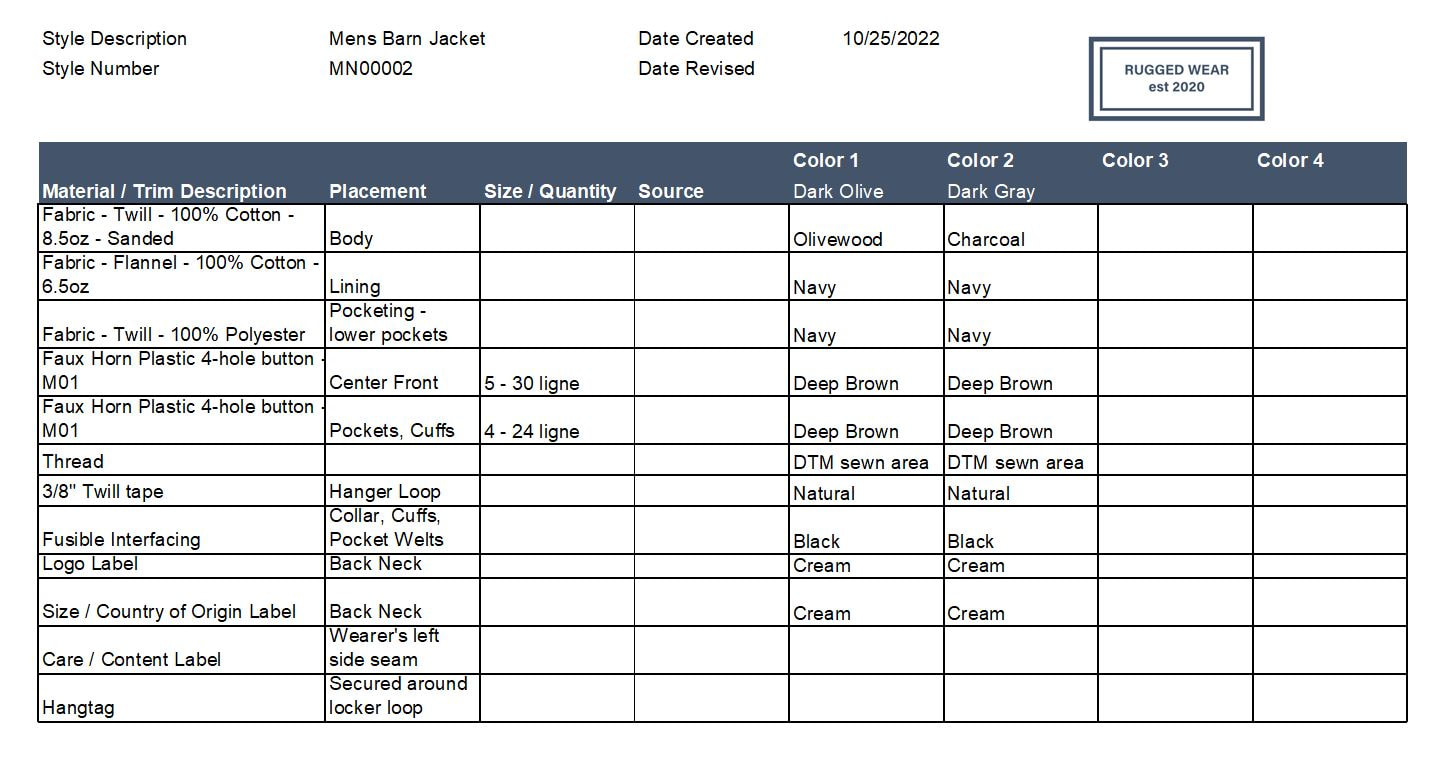

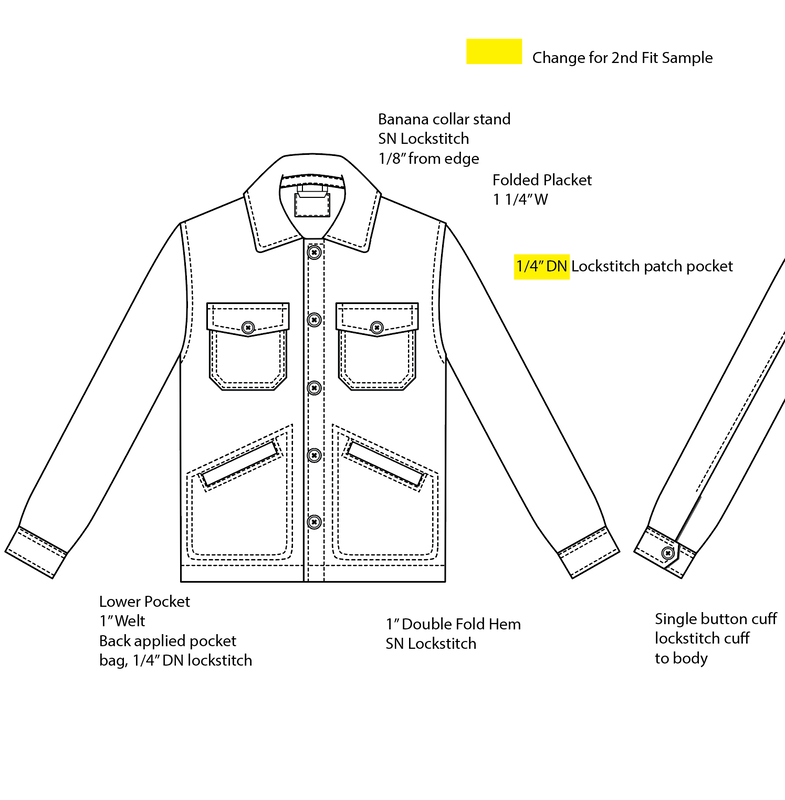

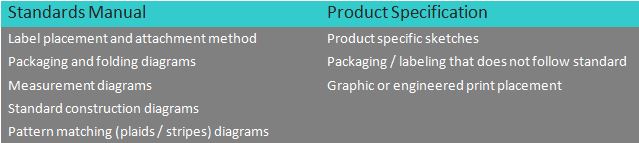

Construction There are two primary ways to handle construction in a tech pack. The first is to show the visible construction elements on the illustrations and add callouts showing key construction elements like the width of the hem or topstitch. This method is followed by most retailers in the US and allows the factory engineer to finalize the actual order of operations. The second method to handle construction is to write the actual orders of operation and list the stitch and seam methods. This is useful when working with a cut and make only factory that doesn’t have the internal abilities to find the best construction methods. But many designers and even technical designers do not have the knowledge base to determine a full order of operations. They also may not have visibility to the machines and therefore stitches available at each factory. Bill of Materials This is a list of every component of the garment. The fabric, trims, hangtags, labels, etc. Absolutely everything should be listed. This is usually done in a spreadsheet format. The bill of materials (BOM) may specify specific sources, which is known as “closed” or may be “open” and allow the factory to select the sources. The color of each component should also be listed. The location of each component is necessary on complex garments. If there is a center front zipper and a pocket zipper listed, the factory needs to know which one to use at each location. Garment Measurements The garment measurements should represent the finished measurements of the garment after sewing and any finishing processes such as garment washing to remove shrinkage. Therefore, the measurements may not match the measurements of the paper pattern. In my opinion the garment measurements should include the graded measurements for all sizes from the beginning of development. This allows the factory to accurately calculate fabric utilization and calculate the costs. As the style moves through the development process, each fit sample should be measured and the graded measurements should be revised as changes are made. You cannot control the whole fit of a garment through measurements. This is why companies focused on fit should also be reviewing patterns as part of the fit process. The final graded measurements are also used to audit the quality of the production garments. Factories may designate some points of measurements as “critical” to be audited while other points of measurement are only used for development. How each point of measurement is to be taken can be shown as an illustration in each tech pack or within a standards manual. The choice of method depends on the scale of the organization and how frequently new factories are used. Packaging and Labeling Information about how the garments will be packaged and labeled can be incorporated into the tech pack in a variety of ways. The components can be listed within the bill of materials. How to fold the garments or how to attach labels and hangtags is usually shown through sketches. Larger organizations that are packaging many styles the same way may want to communicate through a standards manual instead of including the same diagrams in a tech pack for every style. A manual can depict how to fold all knit shirts or how to attach hangtags for all woven pants. The Flow of Communication As the style is developed the tech pack evolves and changes. Usually, the initial flow starts with the designer adding sketches. The designer will then review with the technical designer, product developer and/or sourcing team. The technical designer will then create initial garment measurements. The designer may have add some information to the bill of materials stating the desired fabric, but the sourcing team will be more specific once they locate the exact fabric from a mill. Once the tech pack contains enough information it can be passed to an independent pattern-maker or the pattern-maker and development team at the factory. They will review and hopefully ask for any clarifications. Encourage questions. I would rather clarify and update a tech pack at this stage than receive an incorrect first sample. We are only human. Mistakes are common. The tech pack is a working document and will then be updated as the development process progresses. The garment measurements may change as samples are fit and adjusted. The bill of materials may become more specific as trims and suppliers are finalized. What if I Don’t Have an Experienced Team If you are a start up with a great product idea but no experience you need to find the right people. You can hire designers, tech designers and sourcing staff separately or find a firm that will help you with all the steps. Be wary of factories who say they will handle it all for you. Outsourcing work to the factory can be convenient but you can also lose ownership of the process and likely some of your intellectual property. Look for people who will create the sketches, technical packages or patterns if needed as a service. Your contract should state that you retain the intellectual property including the tech pack and patterns. I don’t want you to be the future client who tracks me down to create a consistent fit because multiple factories handled your development and you have products that don’t fit the same. If you are a designer and want to start the tech pack yourself, great. There are templates you can download or you can create your own. Know your limits. Don’t try to create graded garment measurements unless you have the experience to do so. Do I Need Product Lifecycle Management Software (PLM) If you are starting out, you don’t need to invest in software. Software systems or simple templates can be helpful by prompting you to complete all the elements of a tech pack and speed up the process. If you are only developing 5-10 styles a season, you can start with Excel or Google Sheets. Create the sketches in Adobe Illustrator and copy screen shots into the spreadsheet file. I do not recommend trying to create an entire tech pack in Adobe Illustrator. You can’t update written text and garment measurements easily. When do you want to move to a PLM system? If you are creating new styles by making changes to existing styles frequently, PLM allows you to copy and then update only the necessary information. PLM also allows you to manage elements without manually updating every technical package. For example, if you have 10 styles using the same fabric and you decide to change the fabric weight for the next season; then you only need to update the fabric information in a library and it will automatically update on all 10 tech packs. PLM systems also allow you to generate reports and track the progress of styles through the development cycle. Tips After years of working on tech packs, I can share a few tips. First, only list the information in one spot. If you stated the neck trim was 5/8” high on the measurement specs, don’t also list 5/8” on a construction image. Listing information in two or more places invites error. If you change the neck trim to ½” after a fitting and remember to update the measurement specification but forget to update the sketch; the factory won’t know what to do. Or they will waste hours e-mailing and then waiting for a response. Then you will need to update the tech pack again and resend it. Save yourself the grief and don’t repeat information within the tech pack. Be clear what was changed. If you update information, have a clear process to show the factory what changed. Remember, the activities you were given as a kid “spot the five differences”? They might be fun when you are a kid but your factory doesn’t want to spend hours comparing the previous tech pack to a revised tech pack. Your system might be to write out all changes in the fit comments. You might include a history page to track all changes. Or you can highlight and color code construction information that changed. My final tip is to have a Final or Approved status that changes before the factory proceeds to production. This is a last trigger for everyone to review and proof the tech pack before manufacturing. The final tech pack becomes your contract with the factory. Ideally, you’ll have someone evaluating the quality of the products upon receipt against the tech pack.

Good luck and don't skip technical packages!

1 Comment

No one wants to read a thirty page technical package. I certainly don’t want to write a thirty page apparel specification. So how do you convey all the necessary details to a factory in the most concise manner? Communicate visually. Use flat sketches, construction diagrams, images of trims, inspiration images, 3D images to all tell a story. Ask yourself what images the contact person in the factory needs to create an accurate mental model of the garment. Those images need to be powerful enough to snuff out assumptions formed from previous experience or cultural context. Do not repeat or conflict yourself. Information in the style specification should not ever conflict and should not be redundant. Detailed construction sketches should not conflict with the style sketch. If a detailed diagram of a pant fly closes left over right but a sketch of the front of the garment shows it right over left, you have a 50% chance of getting what you want. If a bill of material clearly defines the fabric and trims, do not restate the fabric or trim descriptions on a diagram. Once is enough and reduces confusion. If you change your mind, you will only have to update one item in the specification before reissuing the specification to the factory. Leverage a standards manual. If information is included in the standards manual, do not add the same diagram or information to the specification. Save effort by condensing diagrams that apply to all garments of a certain type into the standards manual. If you are afraid the factory won’t find the information in the standards manual reference the page or section of the manual or a link if the manual is on-line. The chart below shows information that can be included in a standards manual versus a product specification. If you are starting a new line and haven’t established standards, include all the information in your first tech packs but start saving the information to a library so you can build your manual. Proof your work. Ask a team member who isn’t as close to the product to look over the specification. Is there anything that is confusing? Are they left with any questions? Once it is proofed and sent to the factory, make it clear that you are willing to answer questions. A twenty-four hour delay to ask a question is better than a two week delay because an assumption was made and a sample has to be recreated and shipped again.

What other tips do you have for creating specifications? How do you save time? Please share in the comments. The designers I work with think I sit at home with kids' activity books where you identify what is different about one image from the other. In my case, it is one sleeve has a cuff and the other doesn't or only one side of the collar has top stitching. Fashion illustration is a wonderful art form and can convey the vision for a clothing line or style. However, the flat sketches used to communicate with a manufacturer need to be free of artistic embellishment. Countless times I've received sample garments from a manufacturer with an issue only to look at the sketch and find the factory followed the sketch exactly. Some basic tips for flat sketches:

There are various opinions on whether to include the inside of the back collar / interior of the garment on a front sketch. I believe as long as the image is clear either way is acceptable.

**If you aren't well versed in stitch types American and Efird has a great resource on their website that shows common stitch types. Feel free to comment with additional suggestions or resources! |