|

I still meet designers pretending they don’t need technical packages. I say pretending because they know they should have a tech pack but they either don’t have time to create a tech pack or don’t know where to start. I hear statements like; “I’m working with a local factory, they said they don’t need one”. “I don’t know how and no one has asked for one”. So, what is a tech pack and why do you need one? The tech pack is a written document that contains information about an apparel style. You will also here it called a specification or spec, Some people refer to the spec as only the finished garment measurements. There are usually a few key elements to a full technical package:

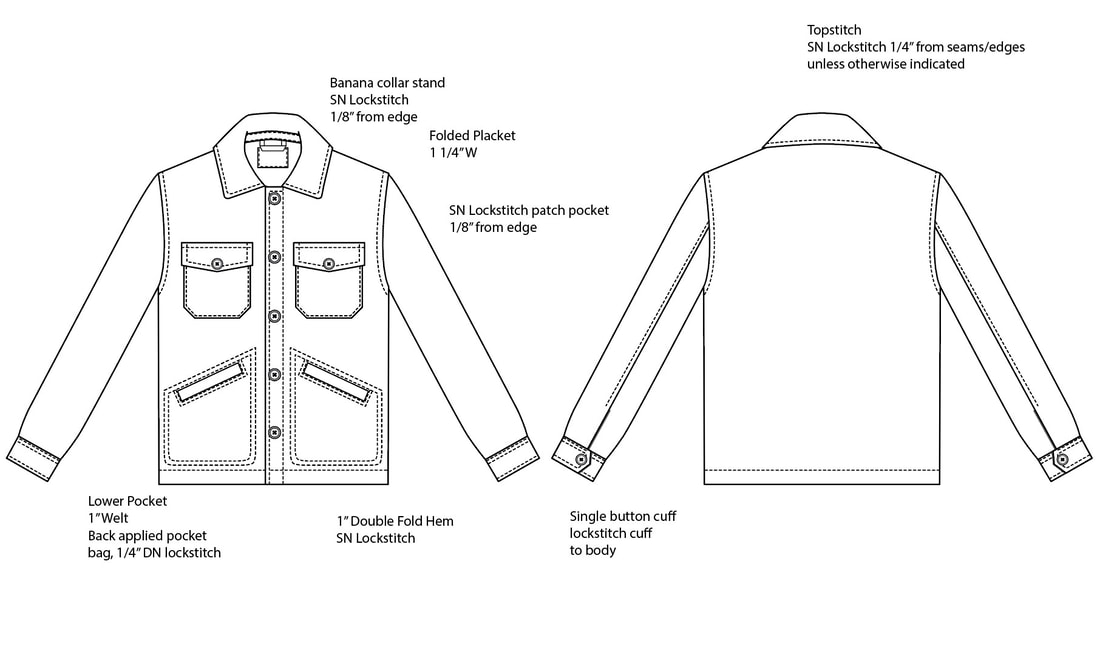

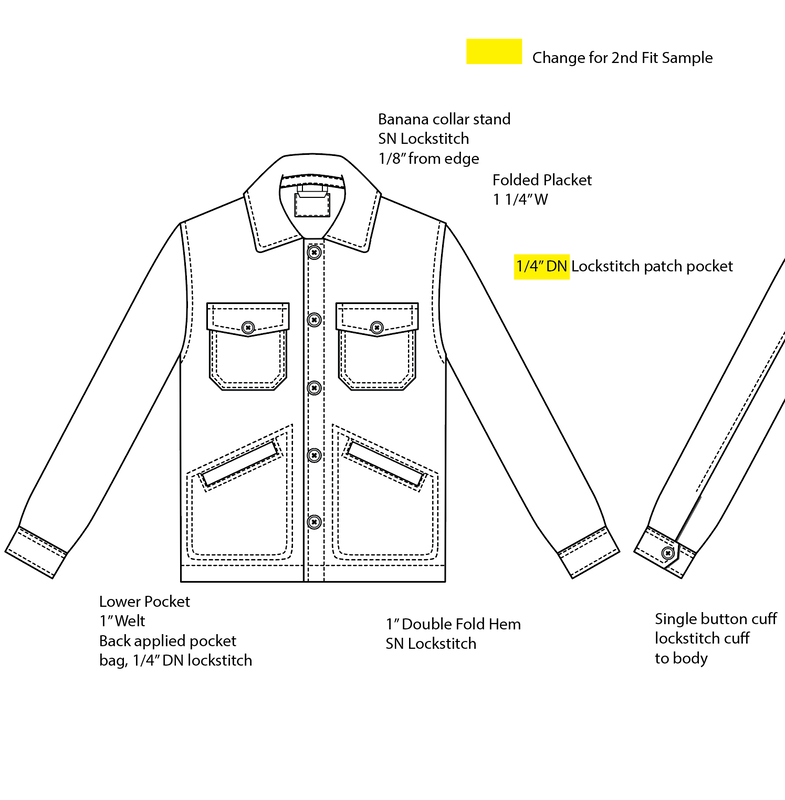

Illustrations The minimum of illustrations is the front and back of the garment. The sketches should include all construction elements, such as topstitching. The sketches should be black and white so all the details can be clearly seen and interpreted. If you want to include colored images, those should be on an additional page. Other images you might include:

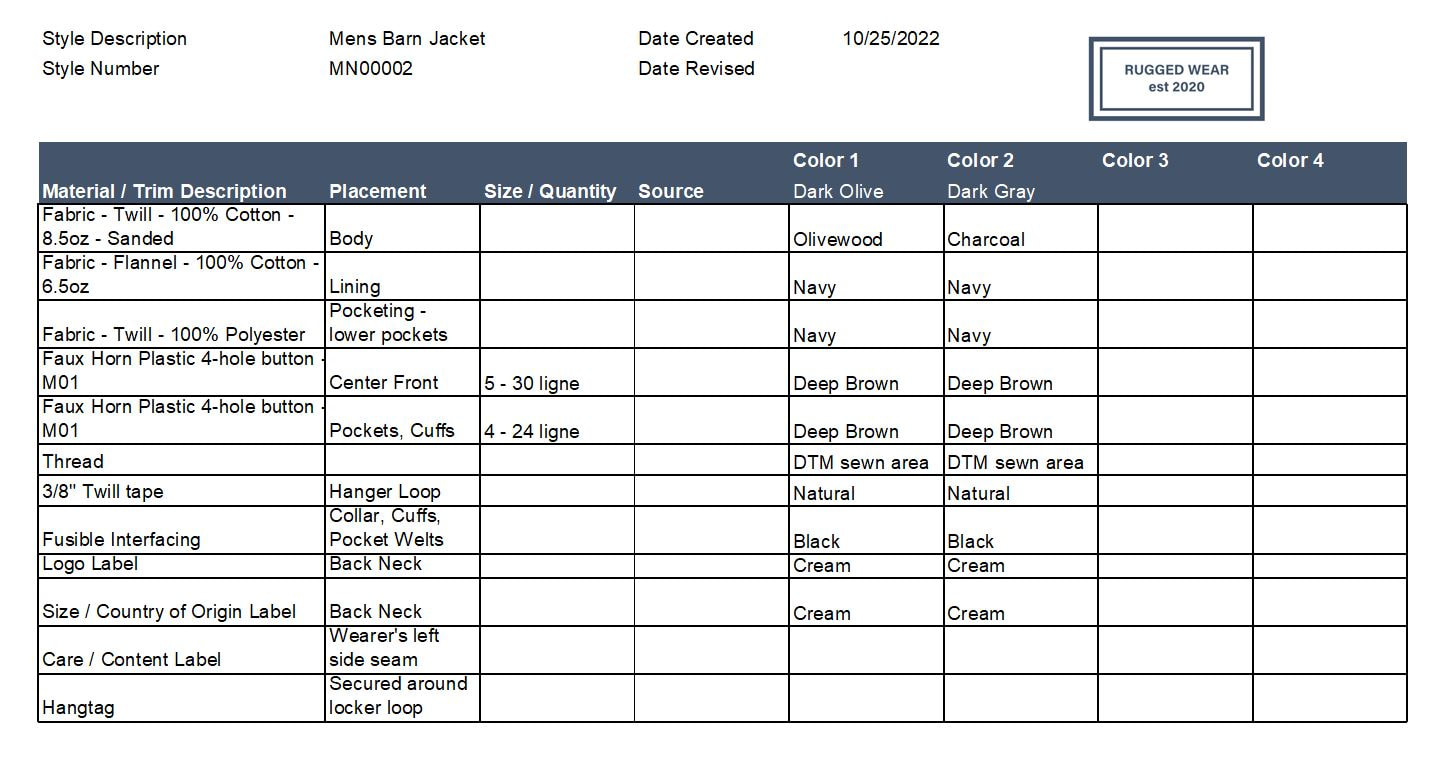

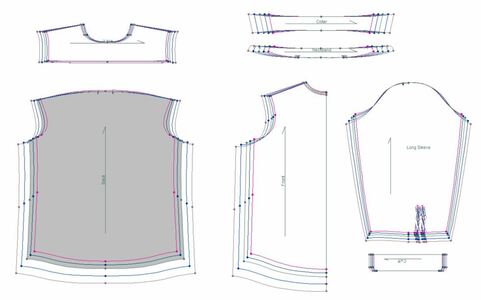

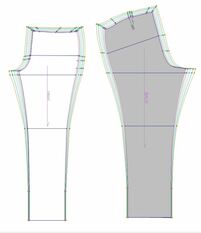

Construction There are two primary ways to handle construction in a tech pack. The first is to show the visible construction elements on the illustrations and add callouts showing key construction elements like the width of the hem or topstitch. This method is followed by most retailers in the US and allows the factory engineer to finalize the actual order of operations. The second method to handle construction is to write the actual orders of operation and list the stitch and seam methods. This is useful when working with a cut and make only factory that doesn’t have the internal abilities to find the best construction methods. But many designers and even technical designers do not have the knowledge base to determine a full order of operations. They also may not have visibility to the machines and therefore stitches available at each factory. Bill of Materials This is a list of every component of the garment. The fabric, trims, hangtags, labels, etc. Absolutely everything should be listed. This is usually done in a spreadsheet format. The bill of materials (BOM) may specify specific sources, which is known as “closed” or may be “open” and allow the factory to select the sources. The color of each component should also be listed. The location of each component is necessary on complex garments. If there is a center front zipper and a pocket zipper listed, the factory needs to know which one to use at each location. Garment Measurements The garment measurements should represent the finished measurements of the garment after sewing and any finishing processes such as garment washing to remove shrinkage. Therefore, the measurements may not match the measurements of the paper pattern. In my opinion the garment measurements should include the graded measurements for all sizes from the beginning of development. This allows the factory to accurately calculate fabric utilization and calculate the costs. As the style moves through the development process, each fit sample should be measured and the graded measurements should be revised as changes are made. You cannot control the whole fit of a garment through measurements. This is why companies focused on fit should also be reviewing patterns as part of the fit process. The final graded measurements are also used to audit the quality of the production garments. Factories may designate some points of measurements as “critical” to be audited while other points of measurement are only used for development. How each point of measurement is to be taken can be shown as an illustration in each tech pack or within a standards manual. The choice of method depends on the scale of the organization and how frequently new factories are used. Packaging and Labeling Information about how the garments will be packaged and labeled can be incorporated into the tech pack in a variety of ways. The components can be listed within the bill of materials. How to fold the garments or how to attach labels and hangtags is usually shown through sketches. Larger organizations that are packaging many styles the same way may want to communicate through a standards manual instead of including the same diagrams in a tech pack for every style. A manual can depict how to fold all knit shirts or how to attach hangtags for all woven pants. The Flow of Communication As the style is developed the tech pack evolves and changes. Usually, the initial flow starts with the designer adding sketches. The designer will then review with the technical designer, product developer and/or sourcing team. The technical designer will then create initial garment measurements. The designer may have add some information to the bill of materials stating the desired fabric, but the sourcing team will be more specific once they locate the exact fabric from a mill. Once the tech pack contains enough information it can be passed to an independent pattern-maker or the pattern-maker and development team at the factory. They will review and hopefully ask for any clarifications. Encourage questions. I would rather clarify and update a tech pack at this stage than receive an incorrect first sample. We are only human. Mistakes are common. The tech pack is a working document and will then be updated as the development process progresses. The garment measurements may change as samples are fit and adjusted. The bill of materials may become more specific as trims and suppliers are finalized. What if I Don’t Have an Experienced Team If you are a start up with a great product idea but no experience you need to find the right people. You can hire designers, tech designers and sourcing staff separately or find a firm that will help you with all the steps. Be wary of factories who say they will handle it all for you. Outsourcing work to the factory can be convenient but you can also lose ownership of the process and likely some of your intellectual property. Look for people who will create the sketches, technical packages or patterns if needed as a service. Your contract should state that you retain the intellectual property including the tech pack and patterns. I don’t want you to be the future client who tracks me down to create a consistent fit because multiple factories handled your development and you have products that don’t fit the same. If you are a designer and want to start the tech pack yourself, great. There are templates you can download or you can create your own. Know your limits. Don’t try to create graded garment measurements unless you have the experience to do so. Do I Need Product Lifecycle Management Software (PLM) If you are starting out, you don’t need to invest in software. Software systems or simple templates can be helpful by prompting you to complete all the elements of a tech pack and speed up the process. If you are only developing 5-10 styles a season, you can start with Excel or Google Sheets. Create the sketches in Adobe Illustrator and copy screen shots into the spreadsheet file. I do not recommend trying to create an entire tech pack in Adobe Illustrator. You can’t update written text and garment measurements easily. When do you want to move to a PLM system? If you are creating new styles by making changes to existing styles frequently, PLM allows you to copy and then update only the necessary information. PLM also allows you to manage elements without manually updating every technical package. For example, if you have 10 styles using the same fabric and you decide to change the fabric weight for the next season; then you only need to update the fabric information in a library and it will automatically update on all 10 tech packs. PLM systems also allow you to generate reports and track the progress of styles through the development cycle. Tips After years of working on tech packs, I can share a few tips. First, only list the information in one spot. If you stated the neck trim was 5/8” high on the measurement specs, don’t also list 5/8” on a construction image. Listing information in two or more places invites error. If you change the neck trim to ½” after a fitting and remember to update the measurement specification but forget to update the sketch; the factory won’t know what to do. Or they will waste hours e-mailing and then waiting for a response. Then you will need to update the tech pack again and resend it. Save yourself the grief and don’t repeat information within the tech pack. Be clear what was changed. If you update information, have a clear process to show the factory what changed. Remember, the activities you were given as a kid “spot the five differences”? They might be fun when you are a kid but your factory doesn’t want to spend hours comparing the previous tech pack to a revised tech pack. Your system might be to write out all changes in the fit comments. You might include a history page to track all changes. Or you can highlight and color code construction information that changed. My final tip is to have a Final or Approved status that changes before the factory proceeds to production. This is a last trigger for everyone to review and proof the tech pack before manufacturing. The final tech pack becomes your contract with the factory. Ideally, you’ll have someone evaluating the quality of the products upon receipt against the tech pack.

Good luck and don't skip technical packages!

1 Comment

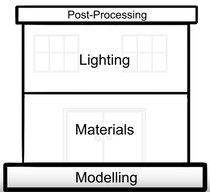

Getting to Today I launched Fireflyline in 2015 with the goal to streamline the product development process. 3D prototypes are serving us well to help clients develop the best products with minimal sampling and improve fit. 3D has become integral to the patternmaking process at Fireflyline. Basic 3D virtual prototypes allow our clients to get an initial idea if their designs are working as desired. Clients appreciate the chance to review and make adjustments before proceeding with physical samples. The design process is iterative and changes are natural. Using 3D has allowed us to move up the stage at which changes are made within the development cycle. Along the way the software we used improved and so have our skills. The virtual prototypes are looking more and more like the physical prototype. We have reached a point where the 3D digital prototype can be used as basic product photography for most apparel types. I use EFI/Optitex software for the bulk of the work to model clothing. When Fireflyline launched Optitex was on Version 15. Last fall we updated to Version 18. During that time the ability to add accurate stitching, use multiple fabric layers without layers colliding, and the accuracy of the fabric shaders/textures has all improved dramatically. Competitive software suppliers such as Browzwear and Clo3D have also made improvements during the same time period. We also stepped out of (or beyond) Optitex for some projects. Working entirely in Optitex for efficiency of development makes complete sense and streamlines the workflow. Yet, for certain projects I wanted more control over the shaders/textures, lighting, and animation. I have been using Keyshot to render models created in Optitex for select projects. There are numerous pros and cons but overall, I like the tool and the results. We also use traditional 3D modeling software to model rigid trims. Keyshot then allows us to realistically render plastics, metal, painted surfaces, and glass. The Ikea catalog is primarily composed of 3D images and has been for several years. There is really no reason why apparel companies can’t do the same for many uses. Majority of e-commerce websites now show the garment without a model for the primary shot. Building Blocks to Photorealism Most apparel companies are approaching 3D as a one stop shop. They purchase software from a single provider and expect the tool to take them from start to finish. The wisest companies realize they need a suite of tools and a variety of skill sets using those tools. I love this image featured in this video by Blender Guru depicting the four building blocks to photorealism. Creating the model of the garment takes the bulk of my time, but accurate materials and lighting are critical to realistic images. The 3D model is only the groundwork for achieving photorealism. Let’s walk through the steps used to create client Constantia Gear’s Disco vest. The lights and power button were modeled in Blender, a traditional 3D modeling software. Each component of the lights is created so that a separate material can be applied to each later. The 2D vest pattern is digitally stitched in Optitex. The hard trims are placed on the model in Optitex. The model is exported from Optitex into Keyshot. Each component of the vest has a material assigned. Colors and shaders are adjusted to accurately represent the physical materials. The appropriate lighting and environment are selected in Keyshot. In this case an indoor studio scenario was used. The lighting used for the 3D image should match the type of lighting a photographer would select for the same scenario. I never complete all steps at once. I’ll finish the model, step away awhile, and then return to do a quality check before exporting and rendering. I often come up with solutions to difficulties while I’m away from the 3D process. Innovation is hard. Not everything works. I spend a crazy amount of time experimenting. Software support staff have been great to offer suggestions to difficulties. But we are sometimes pushing the boundaries of what the software is currently capable of achieving. During this process I’m exchanging images with the client for feedback to achieve exactly what they want. Clients need to advise how they want the garment styled and the type of images they desire. (Note, the software I use at Fireflyline might not be the best selection for everyone. There are a lot of software tools available and some will work better in combination than others. If you are exploring the 3D process, look for the options that work best for you.) Are We There Yet

Have we reached photorealism? Not by my standards, but I’m my toughest critic. However, I think we have reached a point where the average consumer believes the image is the actual product. I wouldn’t currently try to replace lifestyle photography with 3D images, but for ghost photography or shots on a mannequin, 3D digital creations can be realistic. Lighting and shaders/textures look better with every experiment. There are software options available to scan or photograph actual materials to create shaders such as Vizoo and Materialize. I also experiment with altering and combining existing shaders to achieve the correct appearance. Styling the garments can be difficult. Stylists on photoshoots can pin and tweak the appearance of a garment in ways we can’t do in 3D. I cannot quickly switch between buttoned vs unbuttoned, hood up vs hood down, cuffed vs uncuffed. Those options require two completely different 3D models. Using 3D prototypes requires communication, just like the photography process. Communicating with stylists and photographers to plan a shoot requires a shot list, examples of how the product should be styled, and ideas of the mood you want to create. All the same information is required to create a 3D rendered image that you will like. Do not embark down the road of using 3D digital creation to replace photography with the goal of saving time on communication. Advantages Creating a single colorway in 3D may not offer a huge advantage over ghost photography. However, the savings will increase dramatically if there are multiple colors and fabrics planned for a single product. Ghost photography requires multiple photos be taken and several steps in post production. Generally, this must be done for every color. Adding additional colors in 3D is handled in a matter of minutes. Instead of taking new photos of a physical sample and going through the post processing steps again, I can change the RGB codes of the materials and render the new image. If you add a second fabric, the process is similar. As long as the material drapes the same, we only need to change the texture of the render. This can be time consuming a first, but as a library of materials is established the process becomes more efficient. Road Blocks to Progress I would love to see more open communication among those using 3D prototypes for apparel. The problem is usually I and others are working on styles that will not launch for six to twelve months. We cannot share the 3D prototypes with the public until the product launches and by the time we can our capabilities have expanded. I do not want to showcase what I could do six months ago. I want potential clients to see what can be done today. Majority of the images we create for marketing purposes are solely for that purpose, which is additional work. Companies are also hesitant to share because they feel what they have learned and their workflow is a competitive advantage. Fireflyline is in a unique situation because our clients come to us so they do not have to learn new skills or to get up and running in 3D faster. We also do not hesitate to share those skills with corporate clients because doing so builds strong relationships. Unlike many software systems with loads of users there is not a large user community with forums to ask questions and exchange information with peers. Peers, if you are out there and working in 3D for apparel development, please connect! Clients are sometimes puzzled why an apparel pattern-maker or pattern grader asks so many questions. As a pattern grader I want to be sure your designs fit your customers. Your customers should be able to buy the same size each time they make a purchase. The work I do must be both accurate and consistent. The grade should be consistent between the styles I work on and the styles anyone else has graded for you. You might think there are hard and fast rules to grading garments. There are not. Asking questions demonstrates your grader knows what they are doing. No one is questioning the skills of a pattern grader you have used previously. We want to help you create a consistent fit. When should you worry? When your pattern grader doesn’t ask questions. If you tell them you want to run the style in women’s sizes 2-16 and the grader doesn’t ask anything before grading, that is a problem! There is no industry standard for how much each size should grade. You put in a lot of work to get to this point. You have created a garment that fits great in one size. A well graded pattern maintains the integrity of this work across all sizes. A poorly graded pattern jeopardizes all your hard work to date. Questions Your Pattern Grader will ask? What’s your base size? This is the original size the pattern was created to fit. Who is your target customer? Age? Fitness level? Ethnicity? Will the style be alpha or numeric? Alpha sizes are combined sizes, like a women’s Medium (8-10). If alpha which sizes are combined? Equivalent sizes are pretty consistent in the industry for men but alpha size equivalents for women change between brands. A women’s size Medium might be 6-8, 8-10 or 10-12. Size Charts A basic size chart like you use on your website to help your customers find the right size, tells us your basic body width grade. Unfortunately, the size chart usually only gives us basic width measurements such as chest, waist, and hip. The size chart doesn't tell me your customers are mountain climbers in which case I will grade the shoulder width differently than for a brand marketed to seventy-year-old bird watching enthusiasts. Below is a picture of a graded shirt. Each dot is a grade point. You can see the chest, waist, and sweep are only a few of the points graded.  Measurement Charts from Previous Styles If you have been developing apparel for multiple seasons, you may already have a graded measurement chart for the new style you want graded. Your pattern grader should follow that chart. If not, the grader may ask to see charts from previous styles. Measurement charts are usually included in technical packages/specifications. If one person created all previous measurement charts for your brand, they should follow a consistent system. All neck widths should grade the same. All body lengths for knit tops should grade the same. All long sleeves should grade the same. More points are included than the size chart. Previous Graded Patterns The holy grail! Previously graded patterns tell us the grade points on the measurement chart but additional things like the grade distribution and additional grade points that may not be on the measurement chart. Measurements like armhole depth are not frequently included on a garment measurement chart; but help your grader more than the final armhole circumference. Reviewing the grade distribution on pants is especially important. Many people in the industry have different opinions on how much of the grade to place at the rises versus the side seams. I can achieve the same measurements as someone else but the distribution might be different. Usually the goal is to keep every size shaped the same. Occasionally we will break that rule. As an example, we may allow the front rise angle to shift if you think your customers over a certain size have a more pronounced belly. If we ask to see a previous pant you have run; we are only asking to confirm the grading “philosophy” that has been used on your styles in the past. Will we blindly copy your previous patterns? No. If we find something unusual, we will ask you about the issue. There may be a valid reason the pattern is graded that way. But we won’t perpetuate an error. Don’t Worry If You Don’t Have Answers If you don’t have the information requested by the pattern grader, don’t worry. I will gladly help my clients determine the right grading for their target market. I do charge a consulting fee for this work. I do not make the same recommendation to every client. We discuss who your competitors are and the demographics of your target market. I’ll review your competitors’ grades and size charts. I’ll review available anthropometric data for your target market. I’ll grade the type of styles you intend to create before finalizing the grade. Then I’ll create a template that all your measurement charts can be started from to maintain consistency. Sometimes we meet well established brands that have several different factories making products and they have relied on the factory for pattern-making and grading. Unfortunately, I can almost guarantee inconsistencies. Pattern-makers and graders do great work, but every grader and pattern-maker has their own methods. If you are in this situation, you need to create consistent measurement grade rules and graded block patterns. Block patterns are appreciated by graders. They can import a digital block pattern and copy the grade rules directly to the new style. Using graded blocks guarantees consistency in grading. This way you can work directly with the best factory for the product type without worries about consistency. For more information on grading visit our previous post on Reviewing Nested Graded Patterns. For more information on what a block pattern is, we recommend What is a Block from Fashion-Incubator. Copyright 2019 Fireflyline LLC |